Vol 10. The Politics of Policing Women's Clothing + Gender Gap Report

A quick look at the Global Gender Gap report and why things are getting worse and the history of women's resistance to policing of their clothes in South Asia

For our tenth issue, we touch upon the news in South Asia, the Global Gender Gap Report and look at the politics of policing women’s clothes in South Asia. Our Pakistan Editor Anmol Irfan expands on the rich history of South Asian women’s resistance to clothing dictates and what it means by mera jism, meri marzi (my body, my choice).

I do a quick take on the 2021 Global Gender Gap Report. According to the World Economic Forum, at the current relative pace, it will take 195.4 years for South Asia to close its gender gap. Lastly, we highlight some amazing reads, podcasts and shows on gender and South Asia.

Best,

Bansari Kamdar

P.S. If you enjoy reading about South Asia from a gendered lens, you can subscribe below to our bi-monthly newsletter. (Yes, it is free!)

News from South Asia

I talk to Hosna Jalil, the 29-year-old deputy minister of women’s affairs in Aghanistan. Hosna Jalil discusses fighting harassment and discrimination at the workplace and peace talk with the Taliban and the rise in death threats as one of Afghanistan’s highest-ranking female officials. (The Diplomat)

“I want them to understand that if they do something wrong, there is someone who is going to speak about it, she is not going to let it be buried,” said Jalil. “This is my responsibility to the next generation. I have to go through this so my next generation will not have to go through all of these issues. There has to be an end.”

“Nepali leaders unable to accept women in power,” said MP and outspoken gender rights activist Binda Pandey on Nepali women's struggle for recognition in Nepali politics. (Nepali Times)

Bhutanese parliamentarians have recommended 30% nominations for women in politics and other decision-making roles to increase their participation in political, economic and social life. Presently, Bhutan rank 131 out of 153 countries in the Global Gender Gap report 2020, largely due to due to limited representation of women in politics. (South Asia Monitor)

This moving piece on the LGBTQ+ community in Pakistan. It starts with man from Pakistan connecting with another from India on a dating app and their discussion around the decriminalization of 377 in India given the geographical proximity between the two nations. Saad then takes a broader look at the prejudice and discrimination faced by them in Pakistan and ends it on an hopeful note on the resilience of the LGBTQ+ community and how they are carving a place for themselves online. (The Diplomat)

“Even if the law changed, which it never will, trust me, the people are so brainwashed to perceive the word ‘homo’ as the worst [of the sins] that they will burn you and then be rewarded for it by hundreds of millions. You will not be mourned. Your existence is already an inconvenience.”

On March 13, Sarath Weerasekara, Sri Lanka’s minister of public security, announced that the government will ban wearing of the burqa and was quoted as saying that “the burqa” was a “sign of religious extremism” and has a “direct impact on national security.” The burqa ban also follows the controversial forced cremations of over 250 Muslims during the pandemic last year, when Muslims were told that burials could contaminate groundwater. Sri Lankan women have decried the ban as “chauvinistic” and “pure racism” and worry that this will further limit the limited freedom that women have. (Vice News)

“Are [the authorities] stripping us naked in the name of public security? Why has the Muslim women’s body become the battleground for the government? Is it because they want to demonise the Muslim community by abusing its women?” said Shreen Abdul Saroor, a women’s rights activist, to Vice News.

Quick Take: The Global Gender Gap Report 2021

The World Economic Forum recently released it Global Gender Gap Index Report for 2021 that benchmarks the evolution of gender-based gaps and tracks progress towards closing them for four key dimensions: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment. South Asia is the second-lowest performing regions on the index, followed only by the Middle East and North Africa region.

Read the full report: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2021.pdf

At the current relative pace, gender gaps can potentially be closed in 195.4 years in South Asia.

Most countries in South Asia, except Bhutan, have seen a reversal of their efforts to reduce the gender gap as seen by the figure above. Bangladesh remains the best performing country in the region despite dropping 15 ranks on the global rankings. Notably, it ranks 1st globally in political empowerment where where a woman has been in a head-of-state role the longest (27 years) in the past 50 years.

Bangladesh has has seen the reversal of many of the gains it made on women’s economic participation and opportunity, closed just 41.8% of this gap, 2 percentage points lower than 2020. This is largely driven by the decline is in the share of women among professional and technical workers, where the gender gap on this indicator has widened by almost 10 percentage points.

India has fallen by 28 ranks from 2020 to 2021 on the index and is the third-worst performer in the region, having closed just 62.5% of its gap. Due to its large population, it dominates the region’s overall performance and it had widened its its gender gap from almost 66.8% closed in 2020 to 62.5% this year. Most of India’s decline has occurred on the Political Empowerment subindex, where it has regressed 13.5 percentage points as women’s political drastically fell in the last year women’s earned income is only one-fifth of men’s - putting it in the bottom 10 globally on this indicator.

(Read more on female labor force participation in South Asia)

Only Bhutan and Nepal have made some positive progress towards gender parity this year but Nepal’s rank still falls by 5. Overall, the region scores the lowest on economic participation and opportunity subindex, having closed only 33.8% of the gender gap - the lowest globally. This is largely driven by low female labor force participation in South Asia.

There is also a lot of variation on the economic gap, with Afghanistan having closed just 18% of this gender gap, 44 percentage points lower to Nepal that has closed 63% of this gap. India and Pakistan have only closed 31.6% and 32.6% respectively and Bangladesh is ahead closing 41.8% of its gap.

Political Empowerment subindex where the region used to perform well in the past has seen a further decline, down by over 10 percentage points from 38.7% closed last year to only 28.1% of this gender gap bridged in 2021. This is once more driven by the deterioration in its populous states with the share of women ministers decreasing from 23.1% to 9.1% in India and in Pakistan from 12% to 10.7%.

In no South Asia country is the share of women in parliament above 33%, with some countries like Sri Lanka having it as low as 5.4% and 4.6% in Maldives. Afghanistan, Bhutan and Maldives have also never had a woman head of state in their recent history.

(Read more on women and politics in South Asia)

Deep Dive: Mera Jism Meri Marzi, The Breast Tax, and policing of Women’s clothing as a form of control

by Anmol Irfan

Mera Jism Meri Marzi (My Body, My Choice), a mere 4 words that have the power to strike up some very aggressive discourse in Pakistan around the nature of women’s autonomy over their own body, particularly their dressing.

You see, there’s something about a woman’s dupatta - or lack thereof - that is seen as a decision important enough to impact government policy. Just recently, the burqa was seen as enough of a “security risk” in Sri Lanka for a high ranking government official to want to ban it completely. But this isn’t the first time a government in South Asia has decided that its method of control over its citizens will be the clothes a woman can wear.

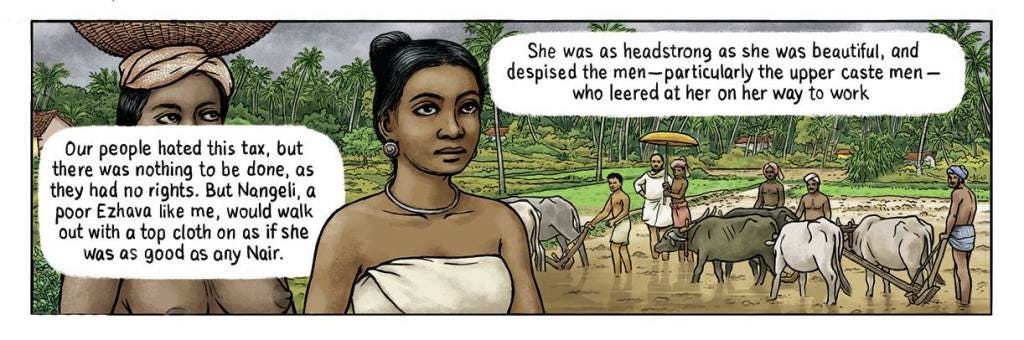

As far back as the 1900s, the king of the princely State of Travancore imposed a fine known as the “breast-tax" that heavily penalized women from lower castes if they covered their breasts. The move was a way to maintain the strict caste system in India at the time.

Even a century ago, clothing decreed social structures and this was one way to maintain the social order of the time. But where there is control, there is undoubtedly revolution. Nangeli, a woman who hailed from one of the castes on which the breast tax applied, decided to cover her breasts without paying the tax, and when officials approached her, she decided to do anything but obey. In an act of defiance to the order of baring her breasts, Nangeli cut off her own breasts and bled to death. Her act forced the king to roll back the decree. The young woman had even then decided nothing was worth giving up her bodily autonomy for - Mera Jism Meri Marzi it seems, is hardly something new.

Half a decade later, Pakistani women’s fashion was all the rage from flowy saris to tight teddy’s until the presidency of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq in the 1980s. The following two decades of growing influence of the Taliban in certain areas of society meant that fashion became political - and forcefully unfeminine. Zia ul Haq even commissioned a designer to create a new Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) uniform that was distinctly unfeminine.

Zia may be long gone, but the seeds of control under the guise of religion that he sowed remain. In 2019, authorities in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa attempted to make burqas mandatory for girls in schools, only for the ruling to be revoked when it faced major backlash both from citizens and political opposition. The ruling was revoked because there were enough people who believed in the concept of Mera Jism Meri Marzi that they were unwilling to let the state police what kind of control they could exercise over the young girls of our society.

South Asian clothing is far from homogeneous across the region. From Pakistan to Bangladesh, Nepal to Srilanka, you find saris, sarongs, cholis, lehengas, shalwars, burqas and kinds of outfits most of us probably couldn’t name. With such a rich history of fashion as a part of regional identity, it is undoubtedly scary when federal or regional governments try to politicise clothing choices.

We are a region where Bollywood item songs directed by men that often sexualise and objectify the very women dancing to them are seen as sexy and entertaining but a woman choosing to not wear a dupatta is seen as vulgar. There is far more conversation around the length of a chador than there is about the disgustingly high numbers of rape and sexual assault that are reported, and far more that go unreported.

When the focus lies more on image than actual protection, it’s hard to believe the argument these laws and social norms exist only for a woman’s protection. Why then, should we not own and embody the beliefs of Mera Jism Meri Marzi.

From Nangeli in the 1900s, to the powerful feminine women of the 60s, 70s and 80s who took to the streets, and the strong determined women who have no fear in shouting down the patriarchy, South Asian women have always fought for hamara jism and hamari marzi (Our bodies, our choices). From the Gulabi Gang to the Aurat March, the stand against the patriarchy is here to stay.

Feminist Reading List

Watch Netflix’s anthology of four films that tackle Indian women’s relationships and their intersections with class, caste, gender and disability. The best two are “Geeli Pucchi” that explores the attraction between two women and how they are oppressed differently due to their caste and “Ankahi“ the love story between a housewife and a hearing-impaired photographer.

Sakshi Venkatraman writes on how desi women have been shamed for body hair growing up and are now challenging these racist Eurocentric standards. It looks particularly at the development of these ideals of beauty in the United States and its links to race and immigration.

Listen to Chuski Pop, a fortnightly podcast hosted by Sweety and Pappu. It is an unpologetically feminist podcast on the latest in desi pop culture and current events. It is impossible not to laugh along with the two co-hosts as they dissect the news.

Postcards of Courage: Justice Leila Seth

Justice Leila Seth was a woman of many firsts. Seth was the first woman to top the London Bar Exam. She went on to become the first female Chief Justice of a state High Court in India and the first female judge on the Delhi High Court. She was the first female lawyer to be designated as a senior counsel by the Supreme Court of India.

She was a part of the 15th Law Commission of India from 1997 to 2000 and is renowned for spearheading the change in inheritance laws for women under the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, which finally gave daughters rights in ancestral property in India.

For many years, she chaired the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. Seth was also a vocal supporter of the decriminalization of homosexuality in India. Hear her TED Talk on why she supports women’s inheritance rights:

Thank you for reading and supporting us.

Subscribe to us below and send your comments and reading suggestions:

Bansari Kamdar is the founder and managing editor of Newspaperwali. Kamdar is an independent journalist and researcher who works at the Gastón Institute for Latino Community Development and Public Policy and Harvard University’s Center for International Development. She reports on gender, immigration, security, and political economy in South Asia. She has written for AP News, The Boston Globe, World Politics Review, The Diplomat, Huffington Post, CNN-News18, and more.

Anmol Irfan is a Muslim Pakistani feminist writer and journalist and our editor for Pakistan. She’s the founder of Perspective Magazine, an online Pakistani community platform, and writes about intersectional feminism, social equality, and South Asian society. Anmol has also written for VICE, HUCK, Harpy Mag, and more.